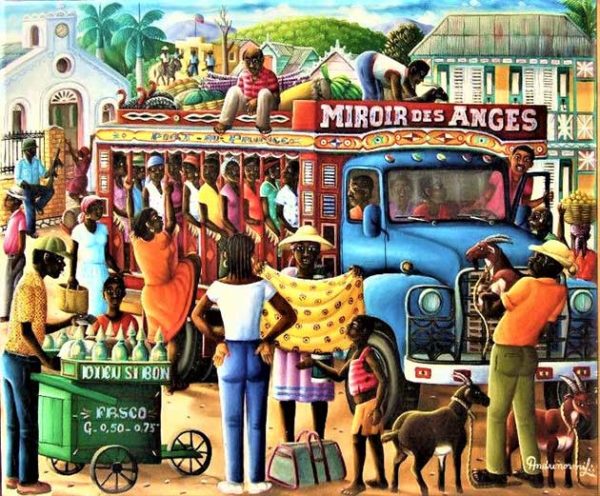

In the northern reaches of Haiti lies a beacon of hope and unity: the New Canal in Ouanaminthe. This ambitious project embodies the resilience and determination of the Haitian people to overcome adversity and pave the way for a brighter future. But it’s not just a canal; it’s a symbol of solidarity, a testament to the strength of community, and a lifeline for economic development.

The Vision

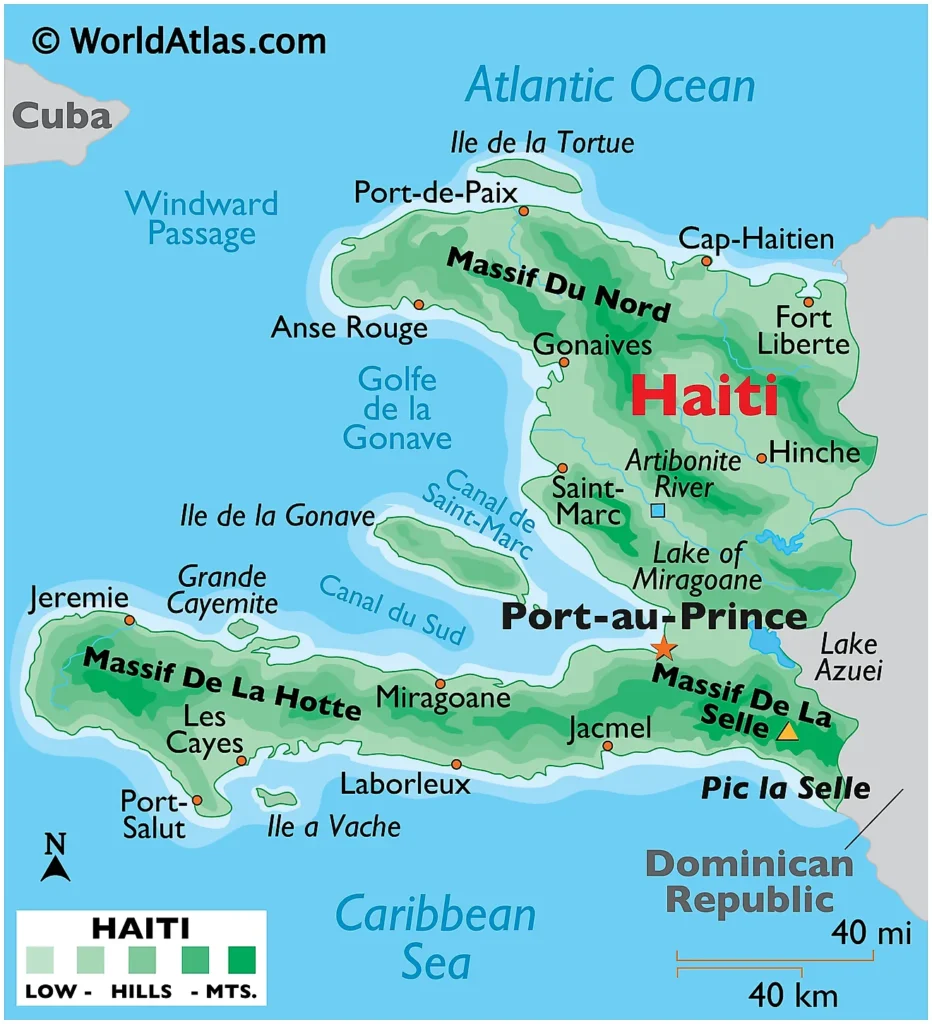

The New Canal project aims to connect the communities of Ouanaminthe in Haiti to the Dominican Republic, facilitating trade and transportation between the two

Current Progress

As of now, the project has made significant strides, with a substantial portion of the canal already completed. However, there’s still much work to be done to bring this vision to fruition. The construction efforts have been largely driven by the local community, with support from both within Haiti and the Haitian diaspora around the world.

Challenges Faced

Yet, the journey has not been without its challenges. The political landscape, particularly the strained relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, has posed obstacles along the way. The current presidency of Luis Abinader in the Dominican Republic has added complexities to the project, with tensions simmering between the two nations.

Resilience and Unity

Despite these challenges, the people of Haiti have demonstrated remarkable resilience and unity. Communities have come together, pooling their resources and labor to advance the construction of the canal. It’s a testament to the strength of the human spirit and the unwavering determination to create a better future for generations to come.

Wideline Pierre: A Driving Force

At the forefront of this movement is Wideline Pierre, a passionate advocate for community development and social change. Wideline’s tireless efforts have been instrumental in mobilizing support for the New Canal project, rallying volunteers, and raising awareness about its importance. Her dedication and leadership have inspired countless others to join the cause and contribute to its success.

Pastor Moise Joseph: A Beacon of Hope

Another key figure in the New Canal project is Pastor Moise Joseph, whose unwavering faith and resilience have kept the movement going even in the face of adversity. Through his guidance and encouragement, communities have remained steadfast in their commitment to seeing the project through to completion. Pastor Moise’s leadership serves as a beacon of hope for all those involved, reminding them of the transformative power of unity and perseverance.

How You Can Contribute

You too can be a part of this transformative project. Whether through financial contributions, volunteer work, or raising awareness on social media, every effort counts. By supporting the New Canal in Ouanaminthe, you’re not just building infrastructure; you’re building bridges of friendship and cooperation between nations.

Diaspora Involvement

The Haitian diaspora plays a crucial role in the success of the New Canal project. From providing financial support to offering expertise and guidance, members of the diaspora are actively involved in shaping the future of their homeland. Their passion and commitment serve as a driving force behind the project’s momentum.

Environmental Considerations

The New Canal project has not been without its critics within Haiti as well. Concerns about environmental impact, displacement of communities, and the preservation of natural habitats have prompted rigorous assessments and mitigation measures. Balancing economic development with environmental sustainability remains a key priority for project stakeholders.

Economic Potential

Once completed, the New Canal is poised to unleash a wave of economic opportunities for both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Improved transportation infrastructure will facilitate the movement of goods and people, boosting trade, tourism, and investment in the region. The canal holds the potential to uplift entire communities, providing jobs and fostering local industries.

Looking Ahead

As construction progresses and the New Canal in Ouanaminthe takes shape, it serves as a testament to the resilience and determination of the Haitian people. Despite the challenges and obstacles encountered along the way, the project stands as a symbol of hope and possibility. With continued support and collaboration, the New Canal will not only connect nations but also forge bonds of friendship and cooperation that transcend borders.

Conclusion

The New Canal in Ouanaminthe is more than just a construction project; it’s a testament to the indomitable spirit of the Haitian people. Through unity, resilience, and unwavering determination, they are building a pathway to prosperity and progress. Join the movement today and be a part of history in the making. Together, we can build bridges, both literal and metaphorical, that connect nations and pave the way for a brighter future.

Aristide went into exile, and a military-led regime ruled the country, committing human rights abuses and suppressing dissent. In response to the political crisis and human rights violations, international pressure and sanctions were imposed on Haiti.

Aristide went into exile, and a military-led regime ruled the country, committing human rights abuses and suppressing dissent. In response to the political crisis and human rights violations, international pressure and sanctions were imposed on Haiti. Cholera Outbreak and Ongoing Challenges: In the aftermath of the earthquake, Haiti faced another crisis when a cholera outbreak occurred in October 2010. The outbreak was linked to a United Nations peacekeeping base, and it resulted in thousands of deaths and further strained the country’s already fragile healthcare system.

Cholera Outbreak and Ongoing Challenges: In the aftermath of the earthquake, Haiti faced another crisis when a cholera outbreak occurred in October 2010. The outbreak was linked to a United Nations peacekeeping base, and it resulted in thousands of deaths and further strained the country’s already fragile healthcare system.